|

|

Formation of Rainbow Bridge | The Cummings-Douglass Expedition | More than a Bridge

|

Description Rainbow Bridge is the world's largest natural bridge. The span has undoubtedly inspired people throughout time--from the neighboring American Indian tribes who consider Rainbow Bridge sacred, to the 300,000 people from around the world who visit it each year. Please visit Rainbow Bridge in a spirit that honors and respects the cultures to whom it is sacred. While Rainbow Bridge is a separate unit of the National Park Service, it is proximate to and administered by Glen Canyon National Recreation Area. For additional information about services and facilities connected with Rainbow Bridge, visit Glen Canyon NRA's Home Page. |

Monument Information Operating Hours/Seasons: Dangling Rope Marina, the closest source of first aid, water, gas, and supplies, is open year-round. A ranger station there is staffed intermittently year-round. Rangers are at Rainbow Bridge daily from Memorial Day through Labor Day, less frequently other times of the year. Weather: Summers are extremely hot with little, if any, shade. Winters are moderately cold with night time lows often below freezing. Spring weather is highly variable with extended periods of strong winds. Fall is generally mild. Temperatures range from 110°F (43°C) in June & July to O°F (-18°C) in December & January.

|

|||||||||

|

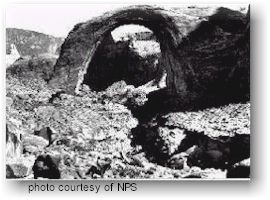

The Beginning The rock formations which comprise Rainbow Bridge are hundreds of millions of years old, deposited in a time when the climate and terrain were very different from what they are today. The base of Rainbow Bridge is composed of Kayenta Sandstone, reddish-brown sands and muds laid down by inland seas and shifting winds over 200 million years ago. The bridge itself is composed of Navajo Sandstone. This slightly younger formation (about 200 million years old) was created as wave after wave of sand dunes were deposited over an extremely dry period which lasted millions of years. These dunes were deposited to depths of up to 1000 feet (305 meters). Over the next 100 million years, both of these formations were buried by an additional 5000 feet (1,524 meters) of other strata. The pressures exerted by the weight of all these materials consolidated and hardened the rock of these and other formations. The Colorado Plateau The landscape that we know as the Colorado Plateau is, geologically speaking, a relative newcomer to the Southwest. The Colorado Plateau is an area of uplifted land, located generally around the Four Corners (the intersection of Colorado, Utah, Arizona, and New Mexico), with the largest sections of the plateau being found in Utah and Arizona. 60-80 million years ago, this area looked very different. It was a relatively stable, flat area. Then, geologic forces began to push the land upward. The greatest and most rapid uplift, however, did not take place until about 5.5 million years ago--a mere breath in geologic time. During this last uplift, the plateau rose some 3000 feet (915 meters) above the surrounding landscape. The uplift buckled the surface of the land. Mountains began pushing up and the earth warped and undulated like an ocean of rock. It began to resemble the fascinating assemblage that is so familiar to us today. But one key ingredient was still to come into play. Water--the Absent Artist When we look at Rainbow Bridge and other spectacular landforms on the Colorado Plateau, we are witnessing a landscape whose principle sculptor was water. Water was not always the infrequent visitor it is today.When the Colorado Plateau uplifted a few million years ago, river gradients were dramatically steepened, especially the Colorado's. These rivers combined their forces with that of the uplift to quickly cut many deep canyons into the plateau. During this time, periods of heavy rains, called pluvials, dramatically increased the amount of water flowing across the plateau. In addition to canyon cutting, water also played a role in other ways, including the formation of Rainbow Bridge. Much of the exposed rock on the plateau, including Rainbow Bridge, is sandstone. Sandstone is really nothing more than grains of sand, some fine, some coarse, bound together by water soluble materials, like calcium carbonate. Whether it's a raindrop or a river, water dissolves this bond and washes away the grains of sand, creating a myriad of fascinating shapes and forms. A Rainbow Made of Stone Initially, water flowing off nearby Navajo Mountain meandered across the sandstone, following a path of least resistance. A drainage known today as Bridge Canyon was carved deep into the rock. At the site of Rainbow Bridge, the Bridge Canyon stream flowed in a tight curve around a thin fin of soft sandstone that jutted into the canyon.

As you can see from the illustration, the force of the stream eventually cut a hole through the fin. Rainbow Bridge was created when the stream altered course and flowed directly through the opening, enlarging it. This process continues to this day, imperceptibly altering the shape of the Bridge. The same erosional forces which created the bridge will, eventually, cause its demise. Rainbow Bridge, along with the rest of the spectacular landscapes of the Colorado Plateau, will exist for only the blink of an eye in geologic time. We should consider ourselves fortunate, indeed, to be witness to these awe-inspiring formations. Let us treasure them while we can.

The Cummings-Douglass Expedition

Finally, late in the afternoon of August

14, the weary riders reached their goal. The rivalry between Cummings

and Douglass had not lessened during the journey, however, and both

men spurred their horses in an attempt to be the first white man to

ride under the bridge. John Wetherill saw what was happening and, being

closer to the bridge, went on ahead and rode under the span. It is unclear

if Wetherill was motivated by diplomacy or irritation, but his actions

did defuse this particular point of contention between Cummings and

Douglass. The two explorers rode side-by-side under the bridge--after

Wetherill. The official "discovery" of Rainbow Bridge

by Cummings and Douglass literally put Rainbow Bridge on the map. Over

the next several years a few hearty adventurers made the formidable

trip, usually guided by John Wetherill. Among those travellers were

Theodore Roosevelt and Zane Grey. Grey later used Rainbow Bridge and

the surrounding country in one of his most famous works, The Rainbow

Trail, though he switched locations of many of the features.

Neighboring Indian tribes believe Rainbow Bridge is a sacred religious site. They travel to Rainbow Bridge to pray and make offerings near and under its lofty span. Special prayers are said before passing beneath the Bridge: neglect to say appropriate prayers might bring misfortune or hardship. In respect of these long-standing beliefs, we request your voluntary compliance in not approaching or walking under Rainbow Bridge. Time For A Change In 1910, it was the geological significance of Rainbow Bridge which caught the attention of the public, and on May 30, 1910, President Taft proclaimed Rainbow Bridge a national monument. But long before its "discovery" by white explorers, Rainbow Bridge was viewed by nearby tribes as a religious site. The significance of Rainbow Bridge to neighboring tribes has become a strong factor in determining the way the monument is managed.In 1995, as Rainbow Bridge National Monument celebrated its 85th anniversary, the Navajo, Hopi, Kaibab Paiute, San Juan Southern Paiute, and White Mesa Ute tribes helped the National Park Service identify and implement culturally sensitive management practices for the monument. In previous years, visitors have walked under Rainbow Bridge. Since 1995, we have asked that visitors, out of respect for the religious significance of Rainbow Bridge, consider viewing it from the viewing area rather than walking up to or under it. Sacred Significance Rainbow Bridge is a sacred place and has tremendous religious significance to neighboring Indian tribes. Rainbow Bridge could be likened to a cathedral--one that nature has sculpted over time. The rock arches and buttresses of Rainbow Bridge inspire feelings of magnificence and reverence in all who see it.Today, we appreciate Rainbow Bridge for its geologic wonder and for its profound significance to the various Indian tribes who revere it. Please treat Rainbow Bridge and the surrounding canyons with respect. Stay on the trail to refrain from trampling plants and land around Rainbow Bridge. Approach and visit Rainbow Bridge as you would a church. Please respect the beliefs of the Indians for Rainbow Bridge. The true significance of Rainbow Bridge extends beyond the obvious. It is indeed a bridge--a bridge between cultures.

|

||||||||||

|

For Additional Information Contact:

Rainbow Bridge National

Monument |

||||||||||

|

For more information visit the National Park Service website |

||||||||||