|

|

The Orchard at Waiilatpu | Native Grasses at Whitman Mission | The "heirloom quilt" of whitmab mission | Adobe in the Northwest? | The Spinning Wheel in the 19th Century | The true story of the Sagers | The Whitman Route | The Great Grave

|

|

|

| Description

Whitman Mission, located in the southeastern part of Washington state, preserves the site of Waiilatpu Mission, a Presbyterian mission to the Cayuse Indians from 1836 to 1847. During the eleven year period of the mission, it also became a way-stop for Oregon Trail pioneers. The mission ended in violence in November, 1847 after an outbreak of measles killed half the Cayuse tribe. Marcus Whitman, Narcissa Whitman and eleven others staying at the mission were killed by the Cayuse. The park preserves the foundations of the mission buildings, the Mill Pond and irrigation ditch, a short segment of the Oregon Trail, and the grave where the victims are buried. Native grasses give visitors a sense of how the area looked in 1840s.

|

Site Information

Hours/Seasons: Summer: 8:00 a.m. to 6:00 p.m. Fall, Winter, Spring: 8:00 a.m. to 4:30 p.m. Closed Thanksgiving, December 25, January 1. Directions: From I-84, travel north on Oregon Route 11 from Pendleton, Oregon to Walla Walla, Washington, then on U.S. Route 12 go west 7 miles. Fees: Weather: Summer: sunny and usually hot; high-low 92-62 degrees F.; wear shorts, T-shirt, hat, and sunscreen. Winter: cloudy and cold; high-low 40-20 degrees F.; wear coat and hat. |

|||

|

The Orchard at Waiilatpu

The Oregon Volunteers arrived at Waiilatpu in March, 1848 and found that the orchard had been destroyed by the Cayuse sometime in the previous three months. The orchard was replanted in 1955 with old-fashioned apple varieties, such as Spizenberg, Northern Spy, Baldwin, and Winesap. Since then trees have been added or replaced as necessary. It still provides a peaceful place to go on warm summer day.

Native Grasses at Whitman Mission  "Waiilatpu"

– the name of the place itself is translated to mean "place of the

people of the rye grass." Among the many native varieties of grasses

that would have been here during Whitman's time, Great Basin wild rye or

giant rye (Elymus cinereus) would have been among the most

abundant. It grows in poor, alkaline soils and is very distinctive growing

3 to 6 feet tall in bunches. "Waiilatpu"

– the name of the place itself is translated to mean "place of the

people of the rye grass." Among the many native varieties of grasses

that would have been here during Whitman's time, Great Basin wild rye or

giant rye (Elymus cinereus) would have been among the most

abundant. It grows in poor, alkaline soils and is very distinctive growing

3 to 6 feet tall in bunches.

Some of the other native grasses that grow at Whitman Mission include – foxtail barley (Hordeum jubatum), streambank wheatgrass (Agropyron riparium), sheep fescue (Festuca ovina), bluebunch wheatgrass (Agropyron spicatum), and reed canary grass (Phalaris arundinacea). The Walla Walla River and the millpond would have provided a habitat for native grass-like plants, such as bulrush or tule reed (Scirpus acutus), and common cat tail (Typha latifolia). Tule was, and still is important to the Cayuse people, their lodges were made of these reeds. Several layers thick, the tules expand when exposed to moisture. The rains never made it through all the layers and provided a dry comfortable place for sleeping and living. Mats made of tules were slept upon and were also usable in other ways. The roots of the tule could be eaten raw or made into a bread. It is still gathered by the Cayuse people today for some of the same uses. The Great Basin wild rye was re-introduced around 1955 to Whitman Mission along with other native plants that had been depleted due to intensive farming. Since then, the revegetation has continued and visitors today can see a great many varieties of plants native to the Waiilatpu of Whitman's time.

THE "HEIRLOOM QUILT" OF WHITMAN MISSION

Every once in a while we still get visitors to Whitman Mission National Historic Site who share these memories of long ago. Often they also comment on the appearance of the land at that time, the adobe bricks from some of the mission buildings still visible despite the grasses, water in the oxbow of the Walla Walla River where the Whitmans' only daughter drowned a century before. Listening to these stories, one realizes how much things have changed over the years. Waiilatpu (Whitman Mission) has been protected by the National Park Service for over 60 years. In that time, it has been expanded and developed, and perhaps just as importantly, a variety of stories have emerged from the soil and from other sources such as diaries and oral traditions. Separately, one can think of these stories of the past as pieces of fabric, each creating a part of the Whitman Mission National Historic Site of today. When sewn together, these small pieces of fabric - the archaeological digs, the diaries of Mrs. Whitman and various pioneers, and other reminiscences create a quilt that is an heirloom treasure. If the complete story is the quilt, the thread that sews the quilt together is the basic story that schoolchildren learn in Washington state history. Waiilatpu was a Presbyterian mission located between the Walla Walla River and Mill Creek in Oregon Country from 1836 to 1847. Marcus and Narcissa Whitman had come from New York to mission to the Cayuse Indians and teach them about God and Euro-American culture. Unsuccessful for the most part in their efforts to teach the Cayuse, the mission became an important way-stop on the Oregon Trail; the Whitmans' assisted many emigrants who otherwise may not have seen their dream of making a new life in the Willamette Valley become a reality. The Whitmans are remembered for being the first to bring a wheeled vehicle across the Rocky Mountains, the first to have a child born of American parents in the Oregon Country, and Narcissa Whitman was one of the first two white women to cross the Rocky Mountains. It was their deaths in 1847 that caused Congress to create Oregon Territory. These threads of the basic story bond together the diverse sources that complete the story of what took place at Waiilatpu and how it is interpreted by park rangers at Whitman Mission National Historic Site. Much of what is interpreted at Whitman Mission has been supplemented through the archaeological excavations done in the 1940's and the 1960's. The building foundations, the irrigation ditch, the gristmill, all were found during this period. Archaeology has been very valuable for learning more about the mission, but the human factor is missing. Finding items such as glassware, broken china, nails, false teeth, etc. do tell us a lot about life at the mission. However, in order to get a complete picture, one can read Narcissa Whitman's letters and find out how she chose glassware and china at Fort Vancouver and was thrilled to be shopping in "the New York of the Pacific;" one can learn that Marcus Whitman was a doctor, perhaps he had the false teeth at the mission awaiting a patient who needed them. With this human factor, one can take a more personal interest in the affairs of the mission. Archaeologists were unable to find the grave of Alice Clarissa Whitman, the Whitmans’ only blood daughter. We find no other evidence of her existence, except through Narcissa’s letters home. If it hadn’t been for these letters, perhaps no one ever would have looked for her grave; as long as the letters survive, the memory of Alice Clarissa Whitman lives on. Many of the visitors to Whitman Mission who are parents of a young child find the death of Alice Clarissa to be the most poignant memory they take home. Standing in front of the oxbow of the Walla Walla River near where the First House once stood, visitors are confronted with life and death, imagining it as it happened that day in June, 1839 -- one of the Indians pulling Alice’s lifeless body from the river, drowned, after going to get water for Sunday supper. They might ask themselves - why did Alice Clarissa have to die? Her parents had been through so much, journeying over a thousand miles from home and family ties in the East to mission to the Cayuse Indians in the Oregon Country - more remote than Hawaii; didn’t they deserve better? Narcissa, crying, consoled herself, praying: "Lord, it is right; it is right; she is not mine, but thine; she has only been lent to me for a little season, and now, dearest Saviour, thou hast the best right to her; ‘Thy will be done, not mine." Reading these words, one can feel the love the Whitmans felt for their daughter. They buried Alice Clarissa near the mission, Narcissa could see her daughter’s grave from the Mission House, the Whitmans’ second residence at Waiilatpu (at the time of Alice Clarissa’s death, they still lived in First House). On a map of the Mission House, she marked the direction of the grave, it gave her comfort to see her daughter’s grave every day. But over time, all evidence of the grave disappeared; park officials wanted to protect Alice Clarissa’s gravesite from construction and mark her resting place. The map gave archaeologists a beginning place in which to look for her grave. Although her grave was never found, a memorial stone was erected near where it was thought to be. During the 1940's, Thomas Garth excavated the Mission House foundation. The archaeology was supplemented by the map of the house that Narcissa Whitman sent home in 1840. Garth found that some of the measurements did not adhere to the original plans, perhaps some modifications were later made to the plans or in the building process. Perhaps Marcus and Narcissa's house plans that were sent back East were somewhat that of "a dream house"; dream houses sometimes change in the reality of the building process. Narcissa told the use of different rooms on the map, she noted the locations of the kitchen, the Indian hall, sleeping rooms, parlor, dining hall, stairs, pantry, cellar, hen house, turkey house, privy house, medicine case, stove, above rooms, and more. This not only assisted with the archaeological investigations, but gave a more complete picture of life at the mission; a lot of work obviously went into the building of these many rooms, and the inclusion of such items such as a hen house and turkey house emphasizes that the mission was also a working farm that was expected to be self-supporting. Those wanting to reconstruct the events at the mission house on November 29 - 30, 1847 (during the Whitman Killings) also could find this map useful, as there would not be much evidence found through the archaeological investigations. The written word brings life to these long past, but not forgotten events. Another piece of fabric that completes the quilt is vistors' and survivors' accounts which tell of the appearance of the mission buildings. Through these accounts, the artist William Henry Jackson (who visited the mission grounds years after the Whitmans died), was able to make a rendition of Waiilatpu, which is thought to be fairly accurate. The appearance of the grounds has changed dramatically over 150 years, sketches and paintings dating to the time of the Whitmans are invaluable to the interpretation of the site. Visitors who come to Whitman Mission National Historic Site are amazed at how green the lawn around the mission site is and how peaceful it is. In order to get an accurate picture of how the mission really was, visitors must use their imaginations. Revegetation of some of the native grasses has helped to make the site more accurate, as does the farm to the west where Whitman would have had his fields. However, there weren't nearly as many trees, and lush grass was probably nonexistent on the mission grounds 150 years ago. The mission would have been very alive with activity of a farm, school, and mission. The Whitmans, the Cayuse, the adopted children of the mission, various workers, and depending on the time of year - the emigrants from the Oregon Trail, all would have been interacting on a daily basis. It was not nearly as quiet as it is today! Just as the whites have memories of Whitman Mission, so do the American Indians who lived here. Their stories are very distinct fabric in the quilt that is very important to its completion. The Cayuse, Umatilla, and Walla Walla people have oral traditions that have been passed down from parent to child over the past century and a half. Some believed that Whitman was poisoning them, causing the measles epidemic that was killing their people. We could excavate Cayuse village sites nearby Whitman Mission to obtain an idea of daily life, including items that had been adopted from Euro-American culture, etc. but we would never learn the thoughts of the people, which are very important to the story of Whitman Mission. Through archaeology alone, we would also know nothing of the traditional origins and customs of the people and how these customs affected the Whitmans. However, with oral traditions, some of which have been written down, we do know the perspective of the Cayuse and what caused them to take action as they did. Long after visiting the site, visitors will remember the moving words of Tiloukaikt, one of the Cayuse hanged for killing the Whitmans: "Did not your missionaries tell us that Christ died to save his people? So die we, to save our people." The quilt of Whitman Mission is made up of the fabric of history. Without archaeology, written works, and oral traditions, our quilt would not look the same. Likewise each person that interprets the story that took place at Waiilatpu adds a little bit to our quilt making its unique design very special. When visitors are able to combine the three components: archaeology (artifacts and building foundations), written words (The Letters of Narcissa Whitman, or other historic accounts), and oral traditions (the descendants of the Cayuse), they obtain a more complete picture of what took place at Waiilatpu 150 years ago and how it fits into the bigger picture that links our site to many other sites within the National Park Service, including Fort Vancouver National Historic Site, Oregon National Historic Trail, and Nez Perce National Historical Park. The more people know about the past, whether it is at Whitman Mission, or the 378 other National Park Service sites, the more likely they are to preserve it for the future. With this more complete multifaceted picture, we hope visitors will make a personal connection to Whitman Mission and take our quilt home in their minds and hearts.

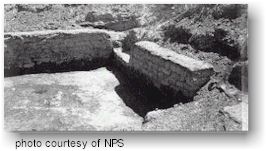

Adobe

structures are typically associated with the Southwest – pueblos, bright

blue sky, desert landscapes – right? Not always! Dr. Marcus Whitman used

adobe for the mission structures he built in the Walla Walla valley of

southeastern Washington. Adobe

structures are typically associated with the Southwest – pueblos, bright

blue sky, desert landscapes – right? Not always! Dr. Marcus Whitman used

adobe for the mission structures he built in the Walla Walla valley of

southeastern Washington.

He had seen similar structures at Fort Boise and Fort Hall on his way west and decided to use it at Waiilatpu, as there was not much wood to be found at the place of the rye grass. The Blue Mountains were rich in timber, but they were 20 miles away. Eventually Whitman built a sawmill on Mill Creek in the Blue Mountains to bring more wood to the mission, but the First House, Mission House, Blacksmith Shop (which used the adobe bricks from the dismantled First House), and Emigrant House were made of mud bricks covered with a whitewash of burned clam shells, as limestone was unavailable. This whitewash helped to protect the structures from the elements. Visitors to the mission site in the 1930's remember seeing several layers of adobe bricks still visible above ground despite years of neglect and weather. A display seen until 1978 at the site of the First House was a wall from the foundation of the building made of adobe bricks that had been uncovered during archeological excavations and was minimally protected by a glass cover. Due to deterioration, the wall was re-covered and preserved in 1978.

The Spinning Wheel in the 19th Century  The

spinning wheel would have been very important in the household of the

typical pioneer family. Not having easy access to economical ready-made

items, the spinning wheel, creating yarn, allowed family members to have

socks, mittens, and in some cases, even shirts and trousers. Making these

items would have cost more time, but less hard earned cash. The

spinning wheel would have been very important in the household of the

typical pioneer family. Not having easy access to economical ready-made

items, the spinning wheel, creating yarn, allowed family members to have

socks, mittens, and in some cases, even shirts and trousers. Making these

items would have cost more time, but less hard earned cash.

In the case of the Whitmans', Mrs. Whitman had easy access to wool for spinning from their flock of sheep, imported from Hawaii. Mrs. Whitman and her adopted children would obtain the shorn wool and go through the many steps to arrive at the final product -- washing, carding, spinning, washing again, dying, and finally knitting or weaving. All those steps for what we can buy at the store today for a fairly reasonable price!

In the spring of 1844, Henry Sager packed his family and goods aboard a covered wagon and headed for the fabled land of Oregon. The Sager wagon joined the others of the emigrant train of that year and slowly the caravan pushed westward from Missouri. Mrs. Sager, already the mother of six youngsters and expecting her seventh, was not at all excited about going to the far West. She had already moved from Virginia to Ohio, then to Indiana, then to Missouri, in order to please her restless husband. Now she dreaded the thought of crossing the Rockies and making the long hazardous trip to the Pacific. At the outset, the daily routine of breaking camp and moving the wagons into line was quickly established. But just as quickly, the Sager family was beset with difficult problems. Soon after starting out, Mrs. Sager presented her husband with a baby girl. While the mother was still regaining her strength, disaster fell upon nine year old Catherine, the oldest of the girls. At Fort Laramie, Catherine caught her dress on an axe handle when she started to climb out of the moving wagon. She fell under the big moving wheels and her leg was broken in several places. Mr. Sager set Catherine's leg and did such a good job that Catherine had only a slight limp after it healed. For the moment, however, the wagon box must have resembled an ambulance, with Mrs. Sager, the new baby, and Catherine all suffering from the jolts and bumps of the trail. Yet, Catherine's accident had one good result. It brought Dr. Dagon into the lives of the Sagers. Dr. Dagon arrived after the leg had been set and checked the break. His help was to become even more important as the wagons moved westward. By the time the emigrants reached South Pass, the gateway through the Rocky Mountains, Henry Sager was seriously ill with fever. His health steadily grew worse despite Dr. Dagon's treatment. By the time the old fur rendezvous of Green River was reached, the Sagers sorrowfully buried their father's body beside the stream. The train had gone too far west for the Sagers to consider turning back to Missouri. Despite the fears of the unknown future, it was easier for the family to go on with the rest of the wagons. Mrs. Sager, not yet fully recovered from child birth and mourning her departed husband, now had all the responsibility for the seven children. She was not alone, however, because Captain William Shaw, who was the leader of that section of the wagon train, and Dr. Dagon made sure that the family was cared for. The doctor climbed into the wagon seat and drove the oxen the rest of the way to Oregon. Slowly, the wagons lumbered along the Snake River and slowly, too, Mrs. Sager sank beneath the cares and sicknesses that hung on her. Overcome by illness, despair, and grief, she was not able to regain her health. She finally became delirious, and as Catherine sadly wrote, "at times perfectly insane." In the vicinity of present day Twin Falls, Idaho, Mrs. Sager said good bye to her children. She asked Dr. Dagon to take care of the orphans until they were safely in the hands of Dr. Marcus Whitman, the well known missionary in the Walla Walla Valley of what is now south-eastern Washington. Sorrowfully, the emigrants buried Mrs. Sager's body. The grief stricken children numbly climbed into the wagon, and Dr. Dagon guided the oxen toward the setting sun. The two boys, John 13 and Francisco 12, were old enough to take care of themselves. But the five girls, Catherine 9, Elizabeth 7, Matilda 5, Hannah Louise 3, and the new baby, needed the care of adults. Despite large families of their own, the women of the wagon train opened their hearts to the orphans and spared what time they could in taking care of the little girls. Several women on the train nursed the baby, so that it survived the weeks that lay ahead of them. This was only the second year that emigrants had taken their wagons all the way to the Columbia. Dr. Dagon, although he immensely enjoyed driving the wagon which had by now been reduced to a two-wheeled cart, was not particularly skilled in driving oxen over the treacherous trail of the lower Snake River. Perched on top of the cart, he urged the oxen on by swearing loudly when he thought that would help. The girls, crowded behind him, had been taught by their parents that swearing was not proper. Everytime the doctor uttered an oath, one of the girls would promptly kick him in the broad seat of his trousers to remind him of their presence. In late October, 1844, the cart pulled into the yard of the Whitman Mission at Waiilatpu. Captain Shaw, who had ridden on ahead to alert the missionaries asked Mrs. Whitman to come outside and see her new children. When Narcissa Whitman ran out to greet the dirty, barefoot orphans, her eyes saw a pitiful sight. Dr. Dagon, his work of father and mother now ended, stood to one side of the cart. Emotion showed strongly on his face as Narcissa murmured soft words of compassion for the ragged, little girls. The two boys, overcome by weariness and relief, began to sob. Catherine, with her crippled leg, also broke into tears, and the smaller children stood dumbfounded and afraid, not knowing what would happen next. The seven orphans had found a new home. Years later, the three oldest girls were to recall many times the loving care of the Whitmans. They were to remember too, that their survival through the wilderness was due largely to the unselfishness of Captain Shaw, Dr. Dagon, and the unnamed pioneer woman. Years later, Catherine wrote, "We were all taken care of by the company. There was not one but that would share their bread with us." In July of the next year, Dr. Whitman obtained a court order in Oregon Territory which gave him legal custody of the children "until further arrangements could be made." But for all practical purposes, the Whitmans had found seven children and the Sager orphans had found a father and mother. Three years after their arrival, in 1841, the Sager children again were orphaned when Marcus and Narcissa Whitman lost their lives when the Cayuse attacked the mission. The two Sager boys, John and Francisco, were also killed. While a captive of the Indians, little Hannah Louise died from sickness. The four surviving girls, after their ransom from the Indians by the Hudson's Bay Company, were moved to the Wilamette Valley in western Oregon where the American settlements were centered. Years later, the three older girls, Catherine, Elizabeth, and Matilda, were to write and speak often of the trip westward and the events at Waiilatpu. They gave high praise to Captain Shaw, the wagon master; Dr. Dagon, who had befriended them; the emigrant women; and, of course, Dr. Marcus Whitman and his wife, Narcissa. Appraisal of the estate of Henry Sager

delivered to Marcus Whitman by Wm. Shaw on the 6th of Nov. 1844

The fore wheels of one wagon------------13.00 One cow---------------------------------37.50 One odd steer----------------------------29.00 One cow (excluding five dollars expended in procuring her from the Indians)---------20.00 3 chains and two yokes-------------------10.00 1 ax---------------------------------------2.00 1 screw plate------------------------------3.00 Total------------------------------------262.50 (sic) June 25, 1845

Solomon Eads Com. B. Magruder

The Whitman Route: Too Tough for the Oregon Trail

This challenge faced Marcus and Narcissa Whitman when they came west in 1836 to establish a Protestant mission among the Cayuse Indians near present day Walla Walla, Washington. Their journey from upper New York state to the Oregon Country was the first made by an anglo family. It proved that women and families could make the journey, pioneering the way for others to follow. When the Whitman's traveled over the Blue Mountains their guide, John McLeod, a fur trader for the Hudson's Bay Company, selected the most direct route possible, suitable for horse and foot travel only. On this route the Whitmans encountered both joy and hardships. The rivers and greenery of the Grand Ronde Valley and the Blue Mountains gave joy, while the terrain provided the challenge and hardships. Narcissa's diary for August 29, 1836, contains this entry, "I frequently met old acquaintances, in the trees and flowers, and was not a little delighted. Indeed I do not know as I was ever so much affected with any scenery in my life... But this scene was of short duration... Before noon we began to descend one of the most terrible mountains for steepness and length I have yet seen. It was like winding stairs in its descent and in some places almost perpendicular... We had no sooner gained the foot of this mountain, when another more steep and dreadful was before us." Tough Terrain In 1843, Marcus Whitman led the first emigrant wagon train of 1,000 people from Fort Hall (near present day Pocatello, Idaho) as far as the Blue Mountains. He then rode ahead to assist a fellow missionary at Lapwai (near present day Lewiston, Idaho). He entrusted the emigrants' safety to Chief Stickus of the Cayuse Tribe, who led them to a trail that wagons could negotiate. It was certainly not the way Marcus and Narcissa and their party had come in 1836. The wagon train of 1843 could not have survived the steep trail the Whitmans used. As the years passed, the Whitmans' route was less used, until finally it was lost. Rediscovering the Route Whitman Overlook

As emigrants began moving westward in the 1840s, Whitman Mission became an important station on the Oregon Trail. For 11 years the mission served both the local indians and the new emigrants. The Whitmans, eleven others and the mission met a violent end in 1847. You can visit the original site selected by Marcus Whitman for his mission. The National Park Service administers this National Historic Site seven miles west of Walla Walla, Washington. Although the original buildings did not survive the years, their locations are outlined on the grounds and outdoor exhibits provide an idea of how the mission must have looked. The museum and interpretive programs at the visitor center will help you understand the events and cultures during Whitmans time.

If you plan on retracing the route of the Whitmans' discussed on this page, take Interstate 84, exit 243 (Mt. Emily and Summit Road) north of La Grande, Oregon. Road 3109 is 9 miles east on Road 31. If you would like to continue exploring the Blue Mountains on your journey, Road 31/Summit Road leads to Highway 204 and comes out between Spout Springs and Elgin, Oregon and provides spectacular views along the way. Take the road slowly as it is gravel and there are many curves. Enjoy exploring the Whitman Route and the beauty of the Blue Mountains.

Walking towards the Shaft Hill from the Visitor Center, there is a fenced off area that is a small cemetery. There is a large marble tombstone with words and names inscribed on what has become known as the Great Grave--

(Please note -- Isaac Gillen's last name should be spelled Gilliland. Jacob D. Hall should be Peter D. Hall). The Great Grave houses the bodies of those killed at Whitman Mission on November 29 - 30, 1847. The grave had been moved several times in the year following the deaths due to wolves or wild dogs digging up the site. Previous to the placement of the marble tomb in 1897, the bodies had only been protected from wild animals by a mound of dirt and an overturned wagon. The current tombstone is in the same location chosen by the Oregon Volunteers in 1848. On the 50th anniversary of what was called the "Whitman Massacre," the bodies were re-interred in the permanent gravesite. William Gray, an associate of Whitman's, had moved on to the Willamette Valley in 1842. After the Whitman's deaths and until his own death in 1889, he tried to raise money for a proper grave and a memorial to the American Board missionaries. Gray was buried in Astoria, Oregon, but was re-interred in 1916 at Waiilatpu, the place he had assisted Whitman in missioning to the Cayuse people.

|

||||

|

For Additional Information Contact: Whitman

Mission National Historic Site

For more information visit the National Park Service website

|

||||